I recently read Thomas Hardy's The Return of the Native. I like writing on books that I've recently read, because it forces me to think deeply about them before I move on to the next book. The first time I tried to write this essay, I failed. It just came out wrong, and I knew it. I failed because I started on a false premise. I believed that I could extract a single, overarching moral teaching from any book I read. This is simply not the case. In reality, three possibilities exist in regards to moral teachings in literature:

There exists no meaning at all. After all, as Frye correctly points out, “what the poet meant to say, then, is, literally, the poem itself”1, and there is no obligation on the behalf of the poet/author to encode any moral teachings in their work.

There exists a single, overarching moral thread (this is what I started with).

There exist multiple meanings. An overarching moral thread may (or may not) be lacking, but various scenes and subplots may have short-lived/minor didactic takeaways.

My failure to produce a good essay the first time around could have been avoided if I had correctly identified The Return of the Native as the 3rd type instead of the 2nd. So, instead of giving you the “one main thing” that Hardy wanted to convey with his book, I will give you a brief summary of the plot, and then tell you what I learned from each of the main characters. If you've read the book, feel free to skip my summary.

Summary

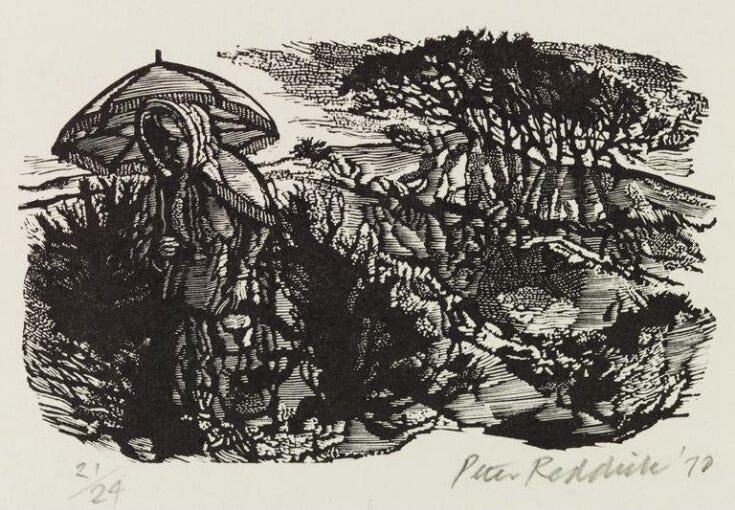

The Return of the Native is set in the countryside of 18th century England. Residents of this countryside live slow and uneventful lives, mostly separated from the bustling life of the city. One resident, beautiful Eustacia Vye, feels the effects of this rural isolation with particular dissatisfaction. Eustacia pines for life's finer things, and her dreams are epitomized in her fantasy of life in Paris. While she has been, and continues to be, stuck in the country, she hopes for a man to take her across the Channel. In the meantime, she philanders with a local inn owner, the noncommittal Damon Wildeve. Wildeve, who likes to play the field, ends up marrying a different local girl out of spite. This girl's name is Thomasin Yeobright. Thomasin is simple, but not necessarily in the intellectual sense: she is low maintenance, and appreciates country life. However, her aunt, Mrs. Yeobright, intuits the mismatch, and publicly disproves of the marriage.

The main plot line of the novel kicks off when Mrs. Yeobright’s son, Clym, comes home for the holidays. Clym had been working in Paris as a store manager, and word spreads quickly of his stately character. Upon hearing that Clym is from Paris, Eustacia becomes enraptured with what she believes him to be, and begins working to arrange an encounter. Surely enough, Clym falls for her beauty, and they are quickly married. Again, Mrs. Yeobright intuits a mismatch, but Clym does not listen. Clym’s sights are set on opening a local school, and he makes it clear to Eustacia before they are married that he will not move to Paris.

Through a series of unfortunate events, tensions rise between Eustacia and Miss Yeobright, and Clym becomes estranged from his mother via association. Misunderstanding and miscommunication reach their peak when Eustacia fails to let Mrs. Yeobright into their house, and Mrs. Yeobright assumes that her son has forever turned his back on her. On her walk home, she is bitten by an adder, and dies. Clym, who found his mother clinging to life on the side of the path, is thrown into a deep depression. His melancholic state is made worse by the testament of a young boy who met Mrs. Yeobright just before the incident, saying that she claimed Clym had broken her heart. After a few months of recovery, Clym discovers that Eustacia had been involved in his mother’s death by not opening the door, and also discovers that Wildeve had been present as well (while Eustacia and Wildeve had ended their relations upon Wildeve's marriage, they had continued to covertly meet with each other). Clym reprimands Eustacia, who throws a fit and moves back to her grandfather's house. Wildeve, who feels partly responsible for the situation, makes Eustacia an offer: he will finance her relocation to Paris. In order to accept the offer, all she has to do is light a signal fire in the next week. One of the caretakers of her grandfather's house unknowingly lights this fire, and Eustacia goes along with fate. The night of the rendezvous, Eustacia, frought with guilt, throws herself into the weir. Hearing the splash, Wildeve and Clym jump in after her. After a short struggle, Eustacia and Wildeve are reunited in death; Clym barely survives.

Clym Yeobright

Clym is a person torn in two directions. He loves Eustacia, but also wants to honor and please his mother. Unfortunately, his situation does not allow for him to have it both ways: he either marries Eustacia or he does not. His choice to marry Eustacia against his mother's advice is perhaps forgivable. Who, if they are honest, has the strength to deny young love? Although it could also be said that if the engagement was prolonged, the warning signs may have shown themselves more clearly, and the fire of young love may have dwindled. Clym’s faults, then, are connected with his youthfulness: he rushes into an ill-matched marriage against the advice of his mother, because he is blinded by Eustacia's beauty. The lesson I learned from Clym was to take things a little slower, and vet your potential spouse thoroughly. Their reputation around town, the advice of parents, and the girl's goals and expectations play a large role in whether or not the marriage will be successful.

Eustacia Vye

Eustacia is a complex character. A cursory reading can cause initial disgust, but I don't think she is fully at fault. Despite her shortcomings, one can also empathize with her; after all, she's had a rough go of things in the country. Her primary flaw is her idealism. Above all things, she loves her idea of Paris, and projects this idea onto Clym. She never truly loves Clym, only ever her projection. Her second flaw is her pride. She cannot bring herself to tell Clym of the door incident, even though it would have saved him from his depression. Additionally, she cannot bring herself to empathize and get along with Mrs. Yeobright; instead, she takes offence and gets hot-headed. Although Eustacia’s emotional turbulence and romantic excess makes up a large part of her character, I do not see these traits as directly responsible for her misfortunes. Rather, I suspect that they would have made her a good match with Wildeve. The lesson that Eustacia teaches is that of tempered idealism:

Do not project ideals onto people. They are imperfect and you will be disappointed. Try to see the real person as they truly are.

Be clear about your ideals. Don’t marry someone who doesn't share them.

Do not deceive yourself into believing that your ideals make you better than others. Other people have their own ideals, and sometimes they are no less noble than your own.

Mrs. Yeobright

Mrs. Yeobright is faced with an ethical and emotional dilemma: does she stick to her beliefs and intuitions, or does she disregard these in order to maintain her relationship with her son? In theory, it is easy to say that she should forgive her son, get over her personal differences with Eustacia, and love them regardless. To some extent, Mrs. Yeobright is also proud, since she believes that her own principles are more important than the feelings of others. It is this pride that causes her relationship with Clym to deteriorate, and it is equally to blame as Clym’s youthful rashness. Mrs. Yeobright showed me the consequences of putting your own idiosyncratic beliefs above close relationships. What's done is done. You’ve done your part. The decision was never yours to make. The best thing to do is forgive and move on.2

Overall, I really liked The Return of the Native. It was a bit slow-going at the beginning, but the latter half made up for it. I will definitely be reading more of Thomas Hardy in the future!

Anatomy of Criticism, p. 87

Often easier said than done!